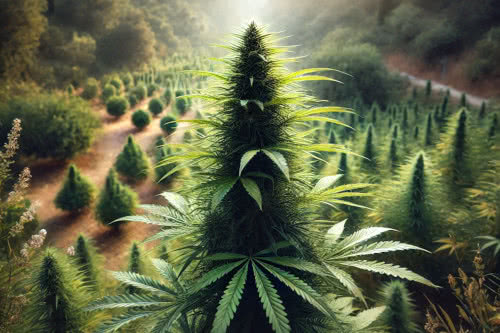

How to Breed Cannabis: Creating Seeds, Crosses and Stable Strains

Comprehensive guide to breeding your own cannabis. Learn how to create unique strains, understand genetics, pheno hunt, stabilize plant traits, store pollen and seeds effectively, and more.

Breeding your own cannabis is a thrilling, rewarding experience filled with experimentation, patience, and sometimes the unexpected. If you’ve ever felt that spark of curiosity about creating your own hybrids—or simply want to preserve the very best genetics in your grow room—this guide has you covered. We’ll explore fundamental plant biology, the tools of the trade, pollination methods, advanced techniques like backcrossing and selfing, feminized seeds, ethical considerations, and wrap it up with FAQs. Let's begin!

Why Breed Cannabis?

Most cannabis consumers begin as smokers or enthusiasts, gradually moving into cultivation—maybe you’ve tried your hand at cloning and grown confident in your horticultural chops. Eventually, you want to push beyond the usual selection of seeds or clones and venture into the realm of breeding your own cannabis.

Reasons people breed cannabis:

- Preservation: Through selective breeding, you can keep cherished genetics alive indefinitely, safeguarding them from seed shortages, industry changes, or a discontinued seed stock.

- Customization: Maybe you want a particular terpene profile (flavors, aromas) combined with a certain yield, height, or flowering time.

- Improving Quality: By handpicking the strongest parental lines, you can gradually strengthen desired traits: yield, pest resistance, drought tolerance, color, aroma, you name it.

- Self-Sufficiency: Seeds can be stored for years, eliminating the need to constantly purchase new packs.

- Pride and Fun: Many cultivators find immense personal satisfaction in creating something brand new—knowing they’ve shaped a cannabis line from seed to seed.

- Artistic Expression: There’s a thrill in creating a strain that only you have!

The best part: breeding is more accessible than you might think. You don’t need a commercial-sized greenhouse or a botanical laboratory. Just basic knowledge, time, space, and a whole lot of enthusiasm.

Cannabis Biology 101

Male vs. Female Plants

Cannabis is dioecious, meaning each plant is either male or female (though occasionally hermaphroditism occurs, which we’ll touch on in a moment). Female plants produce the resinous, sticky buds we love to consume, and they also grow the pistils and calyxes that, once pollinated, develop seeds.

Male plants produce pollen sacs. If these sacs open near a receptive female, pollination occurs, and the female starts producing seeds. Males are rarely kept by home growers unless they’re looking to breed, because a single male can pollinate dozens (or hundreds!) of females, leading to seeded buds. Identifying each gender is crucial:

- Male Plants: Usually taller, fewer leaves, thick stems, and early-appearing pollen sacs (little round balls).

- Female Plants: Typically shorter, bushier, with white pistils sprouting from tear-shaped calyxes.

Because most people want unseeded (sinsemilla) buds for consumption, many growers discard males. However, if you want to breed, you need at least one male in the process—or you can use a feminized approach, which we’ll talk about later.

Hermaphrodites: Good vs. Bad

Hermaphrodites (plants that develop both male and female sexual organs) can be useful in a controlled environment, such as when using colloidal silver or STS to force a stable female to produce male pollen. However, a plant that genetically “herms” under minimal stress is undesirable as a parent—it will likely pass down that weak stability, resulting in seeds that are prone to going hermie themselves.

Stress-induced vs. genetic hermies:

- Stress-induced: If you force a female to produce male pollen through silver-based sprays or extreme environmental stress, you can get feminized pollen. The seeds created can remain stable if the mom is genetically sound.

- Genetic: Some plants carry recessive (or dominant) genes that cause hermaphroditism under normal conditions. Using these as parents is asking for trouble, since “like creates like.”

Regular vs. Feminized Seeds

- Regular Seeds: Produced through natural pollination involving male and female plants, these seeds have roughly a 50/50 chance of being male or female. Growers using regular seeds need to monitor their plants closely to identify and remove males unless breeding is intended.

- Feminized Seeds: These seeds are bred to produce only female plants. This is achieved by encouraging female plants to produce pollen, which is then used to fertilize other female plants. The resulting seeds are almost exclusively female. Using feminized seeds simplifies cultivation by virtually eliminating the risk of male plants and ensuring a harvest of bud-producing females.

Key Concepts of Cannabis Genetics

Genotypes and Phenotypes

- Genotype: The genetic code of a plant—think of it like the blueprint.

- Phenotype: The expression of that code influenced by environment (e.g., color, smell, height). If you plant 10 seeds from the same genetic line, you can get 10 slightly different plants. That’s the “pheno hunt”—finding which phenotype best suits your preference.

Homozygosity vs. Heterozygosity

- Heterozygous seeds (like F2 seeds) can pop out diverse phenotypes, meaning you’ll see variety among siblings.

- Homozygous seeds are more uniform and stable—breeders often aim for high homozygosity so that buyers can count on consistent results, i.e., each seed grown expresses more or less the same traits.

F1, F2…F6, S1: What Do These Letters Mean?

- F1: The first generation of offspring from two distinct parent lines (P1 x P2).

- F2: If you cross two F1 plants of the same lineage, you get an F2, which often shows a broad array of phenotypic variation.

- F3, F4, F5, F6: Successive generations that can become increasingly stable (or sometimes unpredictably varied, depending on selection methods).

- S1: “Selfed” seeds, meaning a female was reversed (caused to produce male pollen) and pollinated itself, leading to seeds with predominantly female genetics.

Terpenes and Cannabinoids

- Terpenes: These are the fragrant oils that confer each strain’s unique smell—whether that’s citrusy, earthy, floral, or skunky. Terpenes also influence the “entourage effect,” modulating how cannabinoids are perceived and felt.

- Cannabinoids: The star compounds include THC (psychoactive), CBD (non-psychoactive), along with many others (CBG, CBC, etc.). Breeding can be used to accentuate or diminish specific cannabinoids for certain medical or recreational outcomes.

Selecting Your Parent Plants

Perhaps the most critical aspect of breeding is selecting your parent plants. Any random cannabis male can pollinate a random female, creating thousands of seeds, but that’s what some call “pollen chucking” as there was no selection process. True breeding means carefully evaluating your plants’ performance and overall stability. This is the pheno hunting process—you want to do some trial and error to find your keepers first.

Stress-Testing for Hermaphroditism

Before you breed with a female, you want to know if she tends to “herm out” under stress. As one Redditor explains:

“Stress induced hermies is good pollen. Genetically induced hermies is BAD pollen.” – u/mrkingpin007

The idea is that you want to separate a truly genetically stable female from one that simply flips male under minor stress. Before locking in parent plants, test them under various stress conditions:

- Minor light leaks

- Fluctuating temperatures

- Lower or higher nutrient levels

- Slightly changing photoperiods, etc.

A great breeding candidate remains 100% female through moderate stress. If it herms easily, it’s probably not worth passing on those unstable genes.

Smoke Test

You may harvest the female, cure the buds, and see how they taste, smell, and feel. If you’re not happy with the results, don’t breed with that plant. Or, if it’s fantastic, you can reveg it or maintain clones for later.

Desirable Traits and Pheno Hunting

- Potency: High THC? Balanced THC/CBD? Rare cannabinoids like THCV or CBG?

- Terpene Profile: Do you love citrus, diesel, or pine?

- Growth Habits: Short, bushy, tall, broad leaves, or narrow leaves?

- Flowering Time: Quick-finishing or slow and steady?

- Resistance: Some strains resist mold, mildew, or pests better.

- Bag Appeal: Colorful buds, heavy trichome production.

Male Selection

Choosing the right male is tougher because you don’t get to smoke-test them. Instead, you observe traits like vigor, structure, smell on the stem rub, overall health, and timing of pollen release. Some advanced breeders do “male flower rosin” or “stem rub” tests to get a sense of the terpene profile.

When you find that perfect female and a robust, healthy male, you’re ready for pollination.

Basic Breeding Methods

Natural/Open Pollination

In nature, cannabis relies on wind to carry pollen from male to female plants. However, if you let a male open its pollen sacs in your grow room, every female in the vicinity can get seeded. That’s ideal if you want a large seed harvest but disastrous if you only wanted seeds on specific branches.

Open pollination has been pivotal in the development and preservation of feral and landrace cannabis strains, contributing to their rich genetic diversity and resilience. However, achieving true open pollination typically requires hundreds or even thousands of plants, making it impractical for small-scale growers aiming for controlled and specific breeding outcomes.

Targeted/Controlled Pollination

To create a small batch of seeds and preserve the rest of your plant for sensimilla buds, isolate a male or collect his pollen in a container. Then, strategically dust chosen branches of your female using tools like brushes or cotton swabs. As u/mygoodies7 explains on Reddit:

“It’s pretty easy to do if you get a male… I just grabbed about 5 qtips and rubbed the pollen all over them... Take those qtips back to some of the ladies you want to pollinate, and rub them on some of the lower buds. … All in all I got about 20 seeds a nug…”

Hand-Pollination and Bagging Techniques

One popular approach is to slip a small paper bag over a branch of the female plant, deposit the male pollen inside, shake gently, then tie it off for a day or two to ensure thorough pollination. Afterward, remove the bag and label that branch. This method keeps the pollen contained to one branch, allowing for multiple breeding projects on a single plant.

Timing for Pollination

The optimal window is when female pistils are well-formed but the buds aren’t too far along. Around weeks 2–4 of flowering is a popular time frame. Seeds often develop within the next 3–6 weeks.

Advanced Breeding Techniques

For those looking to go further than a simple F1 cross, these techniques will help refine your lines.

Backcrossing (BX)

Let’s say you have an especially fragrant female you want to “lock in.” You find a male that pairs decently with her to create an F1 generation, then you select an offspring that strongly resembles the mother. If you breed that offspring back to the mother, you get a backcross (BX). This further cements those mother traits in the gene pool.

Warning: Excessive backcrossing can unearth recessive traits—sometimes negative ones. Keep an eye out for undesirable characteristics, such as mold susceptibility or slow growth.

Line Breeding and Stabilization

Line breeding is when breeders keep a lineage close (often breeding siblings or half-siblings) to reinforce desirable traits across multiple generations. By the F5 or F6 stage, you might have a fairly stable line that throws consistent phenotypes.

Polyhybrids

A polyhybrid occurs when you cross two already hybrid strains. Because each parent is genetically mixed, the offspring carry even more variation. This can produce a kaleidoscope of traits:

- Pros: Potential for highly unique phenotypes with surprising characteristics.

- Cons: The offspring may be unstable, requiring multiple generations to find a uniform line.

Feminized Seeds and STS

Feminized seeds are hugely popular because they produce exclusively female plants. The trick typically involves Silver Thiosulfate Solution (STS) or Colloidal Silver (CS). Both methods temporarily block a plant’s ethylene production. Remember, cannabis produces female flowers under the influence of ethylene. Stop that hormone, and a female plant grows male-looking flowers with pollen that carries only female (X) chromosomes.

STS is usually more reliable. You can follow the Douglas.Curtis guide on ICMag to make your own:

- Mix two solutions: “A” (Silver Nitrate + distilled water) and “B” (Sodium Thiosulfate + distilled water).

- Combine them in a specific ratio to create STS.

- Spray budding sites of a female plant so she produces male pollen sacs.

- Use that pollen to fertilize any female (including a clone of itself).

- Seeds produced are 99%+ female.

If you prefer a pre-made STS mix that's ready to spray, you can purchase it online from retailers like Amazon or select grow shops. Important: Stress-test your female thoroughly. If she naturally herms, you might be passing on hermaphroditic tendencies.

Selfing

Selfing, or self-pollination, is a favored technique among cannabis breeders for rapidly stabilizing their strains. By transferring pollen from a plant’s own anthers to its stigma, breeders can produce seeds without needing another parent. This method ensures that all genetic material comes from a single plant, quickly increasing genetic stability across generations.

How to self your cannabis plant:

- Choose Your Parent Plant: Select a female plant with the traits you want to stabilize.

- Produce Feminized Pollen: Reverse the female plant using STS or CS to generate feminized pollen.

- Self-Pollinate: Apply the feminized pollen back onto the same plant or its clone.

- Harvest Seeds: Collect the seeds produced, marking them as the first generation (S1). Repeat for Stability: Grow the S1 seeds, select the best offspring, and continue the selfing process through subsequent generations (S2, S3, etc.).

Carefully monitor each generation for vigor and undesirable traits to maintain a healthy and stable strain. While selfing is powerful for fixing desirable traits, it can also lead to reduced vigor and the potential fixation of unwanted characteristics.

Collecting and Storing Pollen

Pollen is the key to fertilization. But it’s highly perishable if exposed to moisture or heat. Here’s a quick primer on how to store it for future crosses:

- Wait Until the Pollen Sacs Are Ripe Look for swollen sacs that are starting to crack. If you wait too long, they might open and release pollen everywhere.

- Shake or Tap to Collect Some folks simply shake a male plant over a paper plate or dish. Others put a plastic bag over a branch, shake, seal, and remove.

- Drying Pollen must be thoroughly dry. Introduce a desiccant (like dry rice) in a sealed container for a few days.

- Dilute with Flour (Optional) Many growers mix 1 part pollen with 50 parts flour to help distribute it evenly when brushing onto buds. However, this is more optional if you store pure pollen carefully.

- Freeze in Airtight Containers For long-term storage, your best bet is sealing the pollen (with or without flour) in small vials or foil pouches, placing them in a sealed jar with a desiccant, and storing it in the freezer. Double-check that container is truly airtight.

Always label your containers with the strain name and date so you don’t accidentally dust your prized female with the wrong pollen.

Pollen Control and Preventing Accidents

Accidentally seeding your entire crop is a breeder’s worst nightmare. Use these tricks:

- Separate Tents/Rooms: Keep your breeding tent or chamber completely separate from your main flower space.

- Filter Intakes/Exhausts: Pollen can travel on the slightest breeze, so use filters where possible.

- Water Spritz: A fine mist of water can deactivate pollen in the air. Spray down the space after every pollination session.

- Clean Surfaces Thoroughly: Wipe tents, fans, and walls with soapy water or a mild bleach solution.

“I use a spray bottle of r/o filtered water and spray down the air in the room, any time I disturb pollen. It knocks the pollen out of the air.” – Douglas.Curtis

Breeding for Specific Traits

One of the joys of breeding is selecting for traits that matter most to you. Let’s see how you might do that.

Potency (THC, CBD, and Beyond)

If you want high THC, choose parents known for high THC. Lab testing is ideal, but you can also rely on personal experience or recognized strain reputations. For CBD-rich strains, cross known high-CBD parents to stack that trait in offspring.

Flavor and Aroma (Terpenes)

Terpenes are incredibly important to the cannabis experience. Limonene produces lemony or citrusy profiles, pinene is piney, myrcene is earthy and musky, etc. If you want a unique flavor combo, say a sweet berry meets diesel, pick parents with those distinct terpene signatures.

Growth Habits, Yield, and Resistance

Selecting for yield means picking the bulkiest male and female. Or maybe you grow in a humid environment and need mold-resistant genes—look for those traits in your mother and father. Keep track of how each candidate responds to pests, nutrient levels, and training methods.

Ethical and Practical Considerations

Genetic Diversity

Breeding should ideally help preserve diversity. Monoculture or hyper-focusing on just one strain can lower resilience. Explore older “landrace” or “heirloom” lines to keep historical genetics alive. Including them in your breeding program can preserve valuable traits like disease or pest resistance.

Intellectual Property and Respect for Breeders

Breeders spend years (and often significant funds) stabilizing genetics. While you’re free to buy seeds and breed them at home, it’s courteous to acknowledge the original source if you plan to share or sell seeds. As some Reddit users debate:

“As long as you’re not back crossing the same strain to itself and selling the seeds, you’re straight. Everyone used someone’s genes to start breeding.” – u/Talib215

“If you just take two other breeders’ work then reverse it, that’s very similar to just releasing the original F1. You want to be breeding with your own work as much as possible really.” – u/shwale_

“There's no legal issue, but big companies are trying to own genetics, which is just plain ol evil. A lot of breeders like for folks to ask permission, but if you bought seeds and picked a plant you like, its yours.” –

Still, it’s good form to give credit to the original breeder if you incorporate their line into your project.

Harvesting and Storing Seeds

Once your female has been pollinated, seeds form in the calyxes. This process takes around 3–6 weeks, depending on the cultivar.

Signs your seeds are mature:

- Seeds start bursting from the calyx.

- Outer shell color changes from pale to mottled brown or tiger-striped.

- They easily pop out when you squeeze the calyx gently.

After harvest:

- Dry them in a cool, dark place for a week or two.

- Cure them similarly to how you’d cure buds, but with lower humidity.

- Store in airtight containers in a dark, cool environment (some folks use refrigerators). Labeled well, seeds can remain viable for years.

Getting Started With Your First Cross

If you’ve never done this before, keep it simple. Pick two stable, healthy plants that complement each other. For instance, a pungent, heavy-yielding mother could pair well with a mold-resistant, early-finishing father. Cross them, label them as an F1 line, and grow out a few seeds next season. Observe how those traits combine!

Pro Tip: If you want seeds but also want sinsemilla buds to smoke, pollinate just one branch on each female by hand. Keep that branch bagged for a day or two, then unbag it and lightly mist. The rest of the plant can stay seedless.

Real Stories and Tips from Growers

Breeding, especially on a small scale, can be quite the adventure. Here are a few real-life insights from Reddit:

- Selecting Only the Best “I feel like a batch of seeds of the same strain, especially from a good breeder, should have a lot on lock. I’d take the most vigorously growing male and female and breed them to make seeds. That way no matter what other traits they have, you should get a good harvest for the time invested.” – u/cosmoceratops

- Keeping it Simple “There’s really no trick to it. Put a male and female next to each other, or otherwise get pollen onto the female flowers. The rest will take care of itself. Just be mindful if you’re letting a male spew pollen naturally, it’s going to fertilize ANY nearby female.” – [deleted user]

- Pollen Chucking vs. True Breeding “Get male pollen, put pollen on an early budding female, harvest seeds. There is pollen chucking and then there is breeding, big difference between the two.” – u/dabbinNstabbin

These quotes showcase both the excitement and caution that come with cannabis breeding. Many folks do it simply because they love experimenting. Others aim for something special they can keep for themselves or share with friends.

Conclusion

Breeding cannabis is a journey that blends art, science, and passion. Whether you’re aiming to capture a specific flavor, preserve a rare landrace, or develop the next heavy-yielding, super-potent hybrid, the core principles remain:

- Select quality parents and stress-test for hermies.

- Control your pollination carefully to avoid accidental seed bombs.

- Document everything: keep track of lineage, pollination dates, traits, and resulting phenotypes.

- Have patience: truly stable lines might take multiple generations.

There’s no better feeling than smoking (or sharing!) buds from a plant you personally helped create, from picking the male and female, all the way through collecting the seeds and raising the next generation. This is how many legendary strains got their start—often in a basement, closet, or small greenhouse where a curious grower dared to experiment.

So, gather your favorite genetics, pick up your notepad, and get pollinating. Each seed you produce carries a unique story, and it just might be the next big strain your friends can’t stop talking about. As they say, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.” With cannabis breeding, the rewards are often delightful surprises for both your senses and your sense of accomplishment.

Now go forth and create the strain of your dreams! Good luck, have fun, and may your seeds sprout into incredible, thriving plants. If you approach this with an open mind, love for the plant, and a dash of patience, you’ll do great. After all, the best part of breeding is that the learning (and excitement) never ends.

FAQ

Can I Breed Cannabis in a Small Grow Space or a Closet?

Answer: Yes, you can do small-scale breeding in a limited area, but you’ll need to be extra cautious with pollen control. A single male can pollinate multiple females quickly, so use separate spaces (or a sealed pollination chamber) and thoroughly clean between grows. Small grow boxes or tents can work; just ensure you have a clear plan to isolate males or reversed females from the rest of your crop. Genetics are key as always, so consider growing short strains that take up minimal space.

What Are Some Common Signs of Viable vs. Non-Viable Seeds?

Answer:

- Viable Seeds: Usually firm, dark-brown to grayish with possible stripes or tiger-like patterns. They don’t crush easily between your fingers.

- Non-Viable Seeds: Often pale (whitish-green), lightweight, or soft. They may crack under gentle pressure. If seeds look underdeveloped (tiny and pale), their germination rates are likely to be very low.

Is It Possible to Breed Autoflowers With Photoperiod Strains?

Answer: You can cross an autoflower with a photoperiod strain, but the offspring won’t necessarily retain the autoflowering trait consistently in the first generation (F1). You’d need multiple generations of selection and backcrossing to stabilize autoflower traits. If your goal is a stable autoflower line, be prepared for a longer, more involved breeding process.

Do I Need Advanced Lab Equipment or Genetic Tests?

Answer: Not necessarily. While some commercial breeders use lab testing to confirm cannabinoid levels or genetic markers, it isn’t a requirement for home or small-scale breeding. Hands-on observations—like growth rate, yield, bud structure, and terpene profile—often suffice. However, if you have access to affordable lab testing, it can be a valuable tool to confirm potency and specific cannabinoid ratios.

Can I Cross Strains From Different Breeders?

Answer: Definitely! Many growers do “pollen-chucking” by mixing genetics from various seed banks. Just be sure to label everything carefully. Also, keep in mind that the resulting offspring might not reflect what the original breeder intended; they’re your own creations now, and you can keep or discard them based on whether they meet your standards.

What If I Don’t Want a Large Number of Seeds?

Answer: You can pollinate just a single branch or a few select bud sites. This “targeted pollination” approach yields fewer seeds, meaning you can still harvest sensimilla from the rest of the plant. Use a small bag or paintbrush method to carefully dust specific areas. Proper labeling (color-coded ribbons or tags) helps you remember which branches got pollinated.

Is Indoor or Outdoor Breeding Better?

Answer: Each has pros and cons:

- Indoor Breeding: You have full environmental control—light, temperature, humidity—making it easier to prevent accidental pollinations and stress factors. However, space is often limited.

- Outdoor Breeding: Offers fresh air, plenty of space, and natural light, but you risk unwanted pollen drifting in from other grows. Controlling variables like temperature and pests also becomes more challenging.

Can I Breed CBD-Rich Hemp With High-THC Cannabis?

Answer: Yes, crossing hemp (which is high in CBD and very low in THC) with a potent THC strain is one way to develop balanced (1:1) or other unique cannabinoid ratios. Just note that you may have to work through several generations to stabilize the specific ratios you want. Also, check local laws on growing hemp vs. high-THC cannabis because certain regions regulate them differently.

How Do I Prevent My New Seeds From Germinating Too Soon or Rotting During Drying?

Answer: After harvest, store seeds in a low-humidity environment. Gently dry the entire branch or buds—don’t leave seeds in overly moist material. Keep them in a cool, dark place with moderate airflow (like a cardboard box or paper envelope) for about a week or two before transferring to long-term storage in an airtight container with desiccant packs.

How Do I Keep My Records Straight?

Answer: Consistent labeling and note-taking are crucial. Attach physical tags to plants (or branches) that list:

- The parent strains (or clone IDs)

- The date of pollination

- Any known traits or generation (F1, F2, BX1, etc.) Additionally, maintain a digital or paper log, possibly with photos, to track flowering progress, harvest dates, and any unique observations. This diligence helps you identify the genetic combinations that are truly worth pursuing.

Are There Any Special Nutrient Needs for Breeding?

Answer: Not particularly. Your breeding plants will flourish with the same balanced nutrient regimen used for healthy cannabis growth and flowering. Some growers give a slight boost of phosphorus and potassium to encourage robust flower development, but there’s no universal “breeding fertilizer.” Focus on keeping plants in optimal condition to ensure vigorous pollen and viable seed production.

Is It Safe to Use Neem Oil or Other Organic Pesticides During Breeding?

Answer: Yes, but apply them carefully. Heavy pesticide use may interfere with pollination, especially if it coats male pollen sacs. If you must treat pests or diseases, do so well before the pollen sacs open or before pollinating females to avoid accidental contamination or reduced viability of pollen. Always follow the product’s recommended application guidelines.

What’s the Difference Between a ‘Breeder Pack’ of Seeds and Regular Retail Seeds?

Answer: “Breeder packs” are sometimes offered by companies who want to share a larger number of seeds from the same line—like 20 or more seeds—to encourage pheno hunting and breeding. Regular retail packs might only have 5–10 seeds, sufficient for a personal grow but not extensive enough for large-scale selection. For even larger projects, you can find bulk cannabis seeds at select retailers. If you plan a bigger breeding project, a breeder pack or bulk seeds can offer more genetic variety to explore.

How Many Generations Should I Grow Before Releasing My Own Strain?

Answer: This depends on your personal standards and your audience. Serious breeders often work strains through multiple generations—F2 to F3 to F4, etc.—until they see consistent, stable traits. If you’re only sharing with friends or personal use, an F1 cross might be exciting enough. But if you aim to establish a reputable name, aim for at least F3–F5 (or backcrosses) to minimize variability.

What If None of My Crosses Turn Out the Way I Hoped?

Answer: Don’t be discouraged. Breeding is often a process of trial and error. You’ll learn new things about plant genetics and about your personal preferences every time you pop seeds from your crosses. Focus on detailed record-keeping, keep experimenting with new parent pairs, and stay open to discovering unexpected gems. Even “failed” crosses teach you something valuable about your breeding lines.